From the American Volunteers in the French Foreign Legion 1914-17 Website:

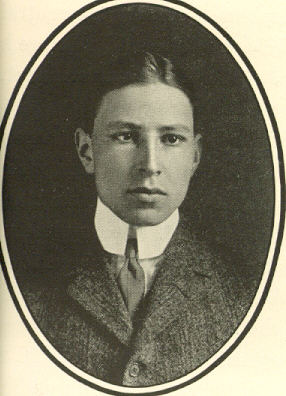

Edward Mandell Stone

Harvard Class of 1908

The first Harvard man to die in the war was completely English; the second was completely American. He was Edward Mandell Stone, born January 5, 1888, at Chicago, Ill., the third son of Henry Baldwin Stone, of the Harvard Class of 1873, and Elizabeth Mandell Stone, both natives of New Bedford, Massachusetts. Henry Baldwin Stone had made for himself a typically American career: on graduation he began work as a machinist in a Waltham cotton mill; then he went West, and entered the shops of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad at Aurora, Ill.; in a few years he became general manager of the Burlington system and second vice-president of the road. Later he was made president of the Chicago Telephone Company and of two other companies representing the great interests of the Bell Telephone system in the central states, a position which he held until a few days before his death. This occurred, July 5, 1897, through an accident. His wife died in 1907.

Their son, Edward, who made his home in Milton, with his mother until her death, and then with his sister, was prepared for college at Milton Academy, and entered Harvard with the Class of 1908. He completed his work for the A.B. degree in 1907, and during his senior year studied in the Law School. He did not finish his studies there, but in 1909 served in the Legation at Buenos Aires as a volunteer private secretary to the Hon. Charles H. Sherrill, United States Minister to the Argentine Republic. Returning to this country he entered the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in January 1910, taking courses in history and political science, and the next autumn resumed his course in the Law School. His graduate work showed marked intelligence and a capability which would have carried him far had he taken up the practice of the law. Of the man himself Mr. Sherrill, speaking of his first interview with Stone upon his arrival in South America, has written:

Br>

He was excessively modest, frankly avowing that he had no delusions as to his mental equipment for making a great success of his life, but in that interview and throughout my subsequent relations with him there always appeared an unswerving integrity of purpose, and a desire to be helpful. Those are the traits which seemed most to mark his character, and those are the traits which later led him to make his life more useful to civilization than our lives will probably be.

This first Harvard volunteer to die for France bore a relation to the war of which there is little to tell beyond a record of his service. Reserved and chary of expression, he was averse equally from letting himself be photographed and from writing about himself in his infrequent letters. He had been living in France for some time before the outbreak of the war, and had become deeply interested in this country and fond of its people. When Germany attacked France in August, 1914, he enlisted at once as a private in the Foreign Legion, 2nd Regiment, Battalion C. In October he was sent to the trenches at the front with a machine-gun section, and served at or near Craonne until wounded there by shrapnel on February 15, 1915. He was taken to the Military Hospital at Romilly, where he died of his wounds on February 27, 1915. He is buried in the Military Cemetary of Romilly. His family have felt sure that his own wish would have been to lie in the country which he loved and served.

His class secretary reports of him that when he received his fatal wound a surgeon asked if he wished him to write to anybody, but that Stone said it was not worth while.

Br>

“These words are, in a way, characteristic of the man. What he did he did well, and invariably felt that no particular attention should be paid to the results he achieved. He was an essentially modest person who took life as he found it, and contributed to everything he took part in both with high ideals and straightforward work.”

The surgeon [Rufus Adrian Van Voast, M.D.] in the Foreign Legion who first cared for him after his wound has written:

I saw Eddie Stone frequently during the six months we were together in “Battalion C, 2ème Régiment de marche du 2ème Etrangère.” He was always on the job and in good spirits: he had a lot of grit, poor chap. One day I got a call from his company to treat a wounded man. It was Stone, I found, with a hole in his side made by a shrapnel ball, which had probably penetrated his left lung. There was no wound exit, so the ball, or piece of shell, stayed in. He was carried back by my squad of stretcher-bearers from the front-line trench—the “Blanc Sablon,” our headquarters—where I had applied the first dressing, and from there removed to a hospital about eight miles back. I did not see him again, and heard that he died of his wound in this hospital. He had friends in the Legion who spoke highly of him to me. There was very little help we regimental could give the wounded, I am sorry to say. All we could do for them was to see that they were carefully moved back out of the firing zone after a first dressing. You can tell his people that he always did his duty as a soldier and died like one. Of this I am sure.

~~ M.A. De Wolfe Howe, Memoirs of the Harvard Dead in the War Against Germany, Volume I: The Vanguard, 1920.

In the Legion, Stone was one of the quietest, hardest-working, and most unassuming soldiers, ever ready to propose himself for any post where coolness and fearlessness were especially required. The other American volunteers saw little of him after the regiment arrived at the front, as he was the only American in his machine-gun section.

Mandell Stone was on guard February 15 with his machine-gun section, at an exposed point in the sector held by his battalion, to the left of Craonnelle. The Germans suddenly started an intense bombardment. Fearing that it was preparatory to a surprise attack, Stone stood by his piece, instead of taking shelter in a dugout, and a few minutes later fell wounded.

Edward Mandell Stone was posthumously cited in the Order of the Army as a “brave Legionniare, who died for France on February 27, 1915, as a result of his glorious wounds received before Craonne.”

PRIVATE CITIZENS SUPPORTING AMERICA'S HERITAGE

American

War Memorials Overseas, Inc.

War Memorials Overseas, Inc.

Stone Edward

Name:

Edward Stone

Rank:

Private

Serial Number:

Unit:

French Foreign Legion

Date of Death:

1915-02-27

State:

Massachuetts

Cemetery:

Romilly-sur-Seine, Community cemetery (Cimetière communal)

Plot:

Row:

Grave:

63

Decoration:

French Army - Order of the Army as a “Brave Legionnaire

Comments: